THE ADMIRAL’S MUCH DISPUTED ANCESTRY

VISITATION OF SHROPSHIRE

Sir Geoffrey Callender and C.J. Britton, 1944

In 1944 the Mariner’s Mirror published an article in two parts titled “Admiral Benbow Fact and Fiction” by Sir Geoffrey Callender and C.J. Britton. These gentlemen set out to “elucidate the truth in regard to his birth, lineage, kindred and related matters.” They drew several conclusions:

1. that the exact date of his birth has not been certified. They note that the Shropshire Parish Registers, Lichfield Diocese, vol. xii, St. Mary’s Parish, Shrewsbury, states in the Preface ‘Admiral Benbow was born in St. Mary’s Parish in 1653 though his baptism is not recorded in the Register.’ They acknowledge that this date is in conflict with his age as stated on his tombstone in Jamaica.

2. Benbow’s birthplace was the tannery at Coton Hill.

3. Benbow’s father was William Benbow, a burgess of Shrewsbury and the owner of the Tannery; and unrelated to the Benbows of Newport, Salop. His daughter Eleanor, Elinor or Helen was the Admiral’s sister.

4. That no genealogical evidence has so far been exhumed to establish a relationship between Admiral Benbow and John Benbow, a Captain in the army of the Parliament, and perhaps a Colonel in the Army of the Crown, who was captured, tried, and shot as a renegade in 1651.

These authors also draw several conclusions regarding the Benbow coat of arms, finding basically that Admiral Benbow had no right to use the Arms confirmed to John Benbow Deputy Clerk to the Crown in Chancery, in 1622/3; but may have used a similar coat of arms. They note the existence of three versions of Benbow arms tied to the Admiral: on his Jamaica tombstone, the tombstone at Deptford of his son John, and the Alms Dish donated by his daughter to the Church at Milton. They hold that as all three could be after his lifetime, therefore there is no direct evidence that he used a coat of arms, and hence no definitive tie to the Newport Benbows.

To draw their conclusions Callender and Britton lean heavily on Owen and Blakeway’s 1825 work: A History of Shrewsbury. Consequently they face the same embarrassment of what to do about Campbell.

Dr. John Campbell, 1747

Dr. Campbell wrote of the Admiral in Lives of the British Admirals and The Naval History of Great Britain(1742) and in an article he contributed to the Biographia Britannica, published in 1747. He used as his sources several of the general historians of the day, newspaper accounts, the Admiral’s journal, and most importantly, interviews with Mr. Paul Calton, Esq., who married one of the Admiral’s daughters, Katherine. Much of the anecdotal information recorded about the Admiral comes from Mr. Calton and is much quoted by later authors. Mr. Calton indicated that he based his information on material passed down from the family to his wife Katherine and other documents that he had gathered.

Campbell states that the Admiral was born “about the year 1650 and was descended of a very ancient worthy and honourable family in Shropshire“. (Biographia, p.676) He says that he was not, as some have suggested, of mean parentage. His father was Colonel John Benbow and the family lost their wealth and status because of their loyalty to Charles 1 and 11. He gives an account of how John and his brother Thomas, both men of estates, joined the King’s service in 1642 as Colonels. He believed that the two were captured at the battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, by the Parliamentary forces and Thomas was shot on October 19 with several other notable gentlemen. Campbell thinks that this “sufficiently shews that the Benbows were then, or had been lately, a very considerable family in Shropshire; for otherwise the Colonel would hardly have been sent out of the world in so good company.” (Biographia, p.681)

According to Campbell the Admiral’s father, John escaped and survived till after the Restoration of Charles 11 in 1660, and accepted a position in the Ordinance of the Tower of very low income. He tells a tale from Paul Calton, which he attests has been confirmed by several other persons of credit. It is to have taken place a little before the 1665 Dutch war. The King had come to the Tower to examine the magazines. There he spotted the good old colonel, whom he had not seen in twenty years and who now had a fine head of grey hairs. The King immediately embraced him.

“My old friend Colonel Benbow, what do you here?”

Benbow replied: “I have a place of fourscore pounds a year, in which I serve your majesty as cheerfully, as if it brought me in four thousand.”

“Alas!” said the King, ” is that all that could be found for an old friend at Worcester? Colonel Legge, bring this gentleman to me to-morrow, and I will provide for him and his family as it becomes me.” (Lives, p.205)

Unfortunately the old man was overcome with the King’s gratitude and goodness, and sitting down on a bench, there breathed his last, before the King was barely out of the Tower. Campbell quips “And thus, both brothers fell martyrs to the royal cause, one in grief, and the other in joy.” Campbell alleges that all the father left the son was his love for the sea, although he sternly denies that the Admiral “was ever a waterman’s boy as some writers have asserted.” He doesn’t explain where his love for the sea originated. He does add that the boy would have been about 15 then and was “bred to the sea”. Benbow’s apprenticeship is however referred to in The Historical and Political Mercury for February 1703 which states:

The Historical and Political Mercury, 1703

“This Rear Admiral John Bembo was born at Shrewsbury in the County of Salop, and bred up in the Free School there: and tho’ the family of the Bembo’s were none of the meanest, yet were they so reduced for their Loyalty that he was bound Prentice to a Waterman: Afterwards he us’d the seas and set up for a Privateer in the West Indies.”

Interestingly, this earliest written reference to the Admiral’s youth suggests that though he had a common upbringing, he was not of low birth in that his family had suffered because of their loyalty. It thus supports Campbell’s thesis though he was not pleased with the waterman apprenticeship. Actually this would have been an excellent beginning as it entailed working on river boats on the Severn which was the life blood of trade and led to the sea. John if 15 when his father died might well have needed to work as an apprentice, especially if the family had lost their estates and had no family business to fall back on.

This 1703 account of Admiral Benbow which appeared in print just months after his death is clearly based on information gleaned from contact with Martha Benbow, the Admiral’s widow. The editor refers to a letter that the Admiral wrote to his wife, and mentions also that the parish where he was born will miss his annual benevolence. Here we have very early evidence connecting Admiral Benbow both to Shrewsbury and to an established family that was reduced because of their loyalty to the crown. The only Salopian Benbow family of note is the Newport branch which included John Benbow, clerk of the Crown whose right to use a coat of arms was confirmed in 1622, and Colonel Benbow, who was shot in 1651 by the roundheads.

Campbell further supports his claim that the Admiral sprang from a noble family by stating that King William:

“granted the Admiral an augmentation of arms which consisted in adding to the three Bent Bows, he already bore, as many arrows, which single act of royal favour, sufficiently destroys the foolish report of his being of mean extraction.” (Biographia, p.676)

T.Phillips, 1779

Campbell was accepted for many years as the authority on the Admiral and was much quoted and utilized in subsequent histories. Just 30 years after Campbell’s account, T. Phillips made a significant addition to Benbow lore, when he published in 1779 his HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF SHREWSBURY. He follows Campbell for the most part, stating that Admiral Benbow was descended of an ancient family in Shropshire, but adds “and born on Cotton-Hill in this town, about the year 1650.” This is the earliest reference, I have yet come across, to the Cotton Hill tradition.

John Charnock, 1795

The next major author of interest is John Charnock who wrote his Biographia Navalis in 1795. Much of what we know of naval captains of that era is due to Charnock’s scholarship. He follows Campbell in suggesting the Admiral is descended from a noble family.

“Many persons have taken uncommon pains to represent this very brave and ever-to-be lamented commander as a person of very mean and despicable origin…The very reverse, however of what has been industriously circulated by many, relative to his origin, is the fact. He is said to have been descended from a family both ancient and honourable.” (Charnock, vol.ii, p.221)

He adds that his grandfather was John Benbow, deputy clerk of the crown in the reign of King James I, an office he held for forty years. Charnock attributes two sons, Thomas and John, to this Clerk of the Crown. Following Campbell, he states both were colonels in the service of Charles the First, and both were captured at the battle of Worcester. He describes Thomas as the Colonel shot in the Castle, and John as the Admiral’s father, who escaped, lived privately till after the restoration, and then obtained a small appointment in the Tower.

The Naval Chronicle, 1809

This grandfather John Benbow was a member of a particular branch of the Benbow family that lived in Newport a town several kilometres from Shrewsbury. This Newport Benbow family is specifically mentioned in the Naval Chronicle of 1809. The author of this memoir of Admiral Benbow commissioned an engraving based on a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller and added to this the Admiral’s Arms. In researching this he had the Herald’s records searched and concluded the following:

“All our naval historians and even the editors of Biographia Britannica, have stated that, on the Admiral’s return from the West Indies, in the year 1700, King William, ‘as a signal mark of his kind acceptance of all his services, granted him an augmentation of arms, which consisted in adding to the three bent bows, which he already bore, as many arrows’. This is an altogether erroneous statement. The Newport branch of the Benbow family, from which the Admiral sprang, bore two bows, and two bundles of arrows, as far back as the year 1623; and, on diligently searching the books in the Herald’s Office, we find that no augmentation whatsoever has been granted to any of the family since that period.” (p.192)

This author, after careful research, did not conclude that Admiral Benbow was not entitled to armorial bearings, only that Campbell’s description was incorrect. And he specifically links the Admiral to the Newport branch of the Benbows.

This is the first scholarly criticism of Campbell’s facts and if accurate would indicate that he was mistaken with regard to the augmentation, a story he received from Paul Calton. This discrediting of Calton’s information was picked up by many subsequent authors and has coloured their assessment of Campbell and the reliability of his information. However, more recent searches of the College of Arms actually supports Campbell’s version: W.R. Benbow approached the College directly in 1998, and Katherine Benbow commissioned Dr. John A. Dick of Belgium to make enquiries of the College in 2000. P.L. Dickenson, Richmond Herald, responded to Mr. W.R. Benbow in February 1998. He indicated that he searched the official registers of the College of Arms from 1530 to the present, and found only one reference to armorial bearings:

P.L. Dickenson, Richmond Herald, 1998

“A shield and crest were recorded for John Benbow(e) of Westminster, Deputy Clerk of the Crown (under Sir Thomas Edmunds) in February 1621 (1622 by modern dating). John Benbow(e) was stated to be the son of Thomas Benbow(e) of Newport in Shropshire. The coat of arms may be described heraldically as follows:

ARMS Sable two longbows palewise endorsed (no tincture is given for the bows, but Or seems the most likely)

CREST On a wreath Or and Sable A harpy Or pierced through the neck by a broad arrow (there are two entries of this crest in our registers, one giving the tincture of the arrow as Argent, and the other as Or)

It appears that the arms were already in existence at that time, although we have no earlier record of their usage. The crest, on the other hand, was newly granted to John Benbow(e), by William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms.”

Mr. Dickenson remarked on the Vincent Papers with the notes on the Visitation of Shropshire in 1623. He refers to the Newport Benbow arms:

” The shield has two longbows, as in our registers, but on either side of them is a shief of three arrows bound together, their points downwards. The crest comprises a harpy, but instead of an arrow through the neck, it has a wreath of roses around the head…..it is of course possible that the Benbow(e) family – or at least some members of it – used this version of the shield and crest, but the official design is the one registered here in 1622“.

W.G.Hunt, Windsor Herald of Arms responded to Dr. Dick in October 2000:

W.G.Hunt, Windsor Herald, 2000

“The records of Grants and Confirmations of Arms from the Tudor period to the present day have been examined for any references to the surname in which you are interested. The following entries were discovered:

1. A Grant of Arms was made to Benbow of Westminster, under clerk of the Crown, by William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms from 1597 – 1623. The Arms were Sable two bent Bows opposite [sic]. The Crest being On a Wreath of the Colours A Harpy Or transfixed with an Arrow also Or. (Camden’s Grants 3.3)

2. A Grant of a Crest is also recorded. It was made to John Benbowe, deputy clerk of the Crown to Sir Thomas Edmunds, and son of Thomas Benbowe of Newport, co: Salop. The Crest being On a Wreath Or and Sable A Harpy Or shot through the neck with a broad Arrow Argent. The Grant was dated February 1621. (Misc. Grants 5.36)”

What is particularly significant is the similarity between the official registered Benbow Arms of two bows and no arrows, and Paul Calton’s description of the Admiral’s Arms as just three bows before the Augmentation of arrows. Calton errs only in the number of bows: ie. three instead of two. It would be quite logical for the Admiral to have discovered the discrepancy between the traditional Newport Benbow Arms and the official registered Benbow Arms.

The simplest explanation is that of a clerical error on the part of the scribe who recorded the official Benbow Arms for the College of Arms in 1621/2, particularly given the traditional depiction of the Newport Benbow Arms in Vincent’s Visitation notes of 1623.

No doubt Admiral Benbow submitted a request to King William to correct this error and inconsistency with an official Augmentation of two bundles of arrows. Probably the College of Arms has no official record of the requested augmentation because of the untimely deaths of Admiral Benbow and William in 1702.

Hugh Owen, 1808

About the same time as the Naval Chronicle article, W.G.Hunt, Windsor Herald, minister of St. Julian’s, Shrewsbury, reinforced the Newport connection in his anonymously published work Some Account of the Ancient and Present State of Shrewsbury (1808). Owen describes the Benbow family as originating in Newport and mentions John, the deputy clerk of the crown in chancery, as the first recipient of a grant of arms. This he described as “Sable, two bows or, stringed argent, between as many garbs of five arrows, of the second, barbed and fleched of the third.” He too notes the difference with Campbell’s description of Benbow’s coat of arms and augmentation by William. Interestingly Owen’s version of the Coat of Arms differs from other authors who generally describe the two bundles holding only three arrows each. Owen adds that it was John’s brother Roger who fathered Thomas and John.

Interestingly Owen transposes the names of the executed Colonel and the Admiral’s father in different parts of his history. In an earlier section of the book he names the executed Colonel as John Benbow and adds that it was John who was the uncle of Admiral Benbow. (p.50-51). Later in the book he switches names and states:

“His eldest son the brave Thomas Benbow, who was born in 1603 rose to the rank of Colonel in the service of Charles 1 and was shot in this town [Shrewsbury] on October 19th, 1651, by sentence of a Court Martial…This may perhaps account for the omission in St. Mary’s register of the baptismal entry of his nephew John, the Admiral, who is said to have been born about 1650.” (p.413)

In this later part of the book Owen adds that tradition has uniformly placed Admiral Benbow’s birth in the ancient house at the foot of Cotton-hill. Also in the later reference he follows Campbell in giving the Admiral’s father as John, the second son of Roger, also a colonel, who lived privately in Shropshire until the restoration when he obtained a small post in the Ordinance at the Tower. With Campbell he relates the death of the Admiral’s father, leaving him an orphan at about age 15. Unlike Campbell he allows that he was reduced to the necessity of becoming a waterman’s boy.

Owen includes another enticing piece to the puzzle of the Admiral’s family. He describes a flat stone at the entrance to St. Mary’s church which has the inscription:

Here Lyeth the Body

of Mrs. Elinor

Hind, Relick of the

Late Mr. Samuel Hind

Grocer and Sister of

ADMIRAL BENBOW.

She departed

this life 24th May

Aged….

To this he adds the entry in St. Mary’s Register: “Elianor Haynes widow buried 30 May 1724.” (Owen, p.419) He notes she kept a coffee house near the church with a portrait of her uncle Colonel Thomas hanging over the fireplace. As well, he relates a tradition that when one of Colonel Thomas’ judges visited her coffee house, he pulled off his glove, and discovered it was covered in blood. The divisions of the Civil war were not lightly forgotten in the Shrewsbury area. These oral traditions clearly support the connection between Admiral Benbow and the Newport branch of the family.

Hugh Owen and John Blakeway, 1825

A few years later the now Archdeacon Owen joined forces with John Blakeway, Prebendary (clergyman) of Lichfield (diocese that includes Shrewsbury) and minister of St. Mary’s, Shrewsbury. They published their History of Shrewsbury in 1825. Blakeway picks up on Owen’s confusion over the name of the executed Colonel, and discovers that Campbell erred in naming him Thomas, as Owen had done in the earlier part of his own History. To this he adds Campbell’s apparent error in his Augmentation of Arms story. This is sufficient to persuade Blakeway to discount entirely Campabell’s account of Admiral Benbow having an attachment to the ancient family of Benbow’s at Newport. Blakeway and Owen pursue the local Cotton Hill connection with speculation based on the Admiral’s sister’s tombstone and limited church records. As a result of their researches they became quite convinced that Campbell’s information was not only erroneous but devious. They lay the blame on his source, Paul Calton.

“The story is extremely well told by Dr. Campbell, but unfortunately is little to be depended on, and some of it, we are sure, cannot have been founded in fact…How such errors should be derived from a source apparently so authentick, is difficult to say…If there has been any intentional misrepresentation in the case, (and it is really not easy to avoid such a suspicion,) one would rather impute it to the weakness of his descendants, than suppose a sturdy seaman capable of being ashamed of his humble origin.” (vol.i, p.470)

Blakeway and Owen base their theory on the gravestone referred to by Owen, in St. Mary’s churchyard, Shrewsbury. At the time of their writing the stone had disappeared. They state it was demolished in 1808. They give the inscription with one addition: where Owen originally could not make out the age, they now have it as unequivocally “79”. This is quite intriguing, since the stone had long since vanished. Based on this age of 79 or 78 they claim to have deduced her birth must have been in 1646. They then point to an entry in St. Mary’s parish which gives for the 7th of July, 1646 “Elinor, daughter of William Benbo, baptized“. They add:

“Her identity is further ascertained by the licence granted by the official of St. Mary’s, March 15, 1672, for her Marriage with John Pernell (her first husband), in which she is called ‘Helen Benbow, aged 26’: so that when we read in the records of the corporation that “Wm. Benboe the younger, of Shrewsbury, tanner, was admitted a burgess on the 17th May 1648, having issue Margaret aged about four, and Elianor aged about two years…we cannot doubt that this was the lady commemorated in the epitaph, and consequently that her brother, Admiral Benbow, was son of William Benbow, tanner, but born after May 1648 when his father had no other issue than the two daughters mentioned above.” (vol.i, p.391)

Furthermore the poor books of St. Mary’s list William Benbow of the Tan-house at Cotton Hill from 1652 to 1664. So Blakeway and Owen supported and developed the tradition that Admiral Benbow was the son of the tanner of Cotton Hill and ran away to sea rather than stay in the family business. This is arguably a possibility. However, their conclusions are not well established, and certainly do not constitute a probability.

Blakeway and Owen make a common error: they assume there was only one Elinor Benbow born around the year 1646. This of course is an assumption that cannot be made, as is evident similarly by the many John and William Benbows of the day. As well, Elinor’s age at death is not quite so firm, if we follow Owen’s original record of the inscription. They may indeed have discovered the actual baptismal registration of the Admiral’s sister, but on the other hand the registration may well be of another person entirely. The English Civil War was raging at the time and parish records suffered greatly as puritans attacked the established Church. As Callender and Britton attest, no birth record has been found of the Admiral himself. I believe it is quite an assumption to discount Campbell’s information solely on the basis of their inferred premises.

Blakeway and Owen add confusion to their theory by maintaining the Admiral’s relationship to the Cavalier shot in 1651 as a Royalist. This forces them to place the Colonel in the Cotton Hill branch without any substantiation. This is a major break with long tradition that has placed him in the Newport line. Despite this they make much of Campbell’s having got his name and rank wrong. They refer to his tombstone which is inscribed:

“Here lieth the body of Captain John Benbow who was buried October 16, 1651.”

As well the St. Chad’s parish record supports this:

“1651, Oct. 16. John Benbowe, Captaine, who was shott at the Castle B.” (vol.i. pp.469-470)

Owen has already demonstrated how easy it is to transpose the names of the executed Colonel and the Admiral’s father. The error in rank is also easily explained.

Callender and Britton point out that John Benbow could have received a promotion from his Parliamentary rank of Captain, when he changed sides and joined the Royalists forces just before the battle of Worcester. They also add the information that John Benbow of the Newport line was baptised 15 April, 1610, so would be an acceptable age of 41 for the rank of Colonel. (Callender and Britton, “Admiral Benbow, Fact and Fiction” p. 133.)

In addition, I point out in Brave Benbow that Katherine may well have been confused by her recollection that the two Colonels were brothers. They would not likely have the same name, and she knew more certainly that her grandfather was named John. Therefore she may have assumed that her Uncle was Thomas, one of the other sons of Roger and Margaret Benbow of the Newport Benbow line. Unbeknownst to Katherine, the two Colonels may have been cousins, rather than brothers. Thus, they could well both have been named John, a common occurrence in my own family. (Brave Benbow, p.24)

In fact, historical records indicate that John Benbow was indeed a Colonel at the time of his death:

1. A pamphlet by Sir Robert Stapylton in 1651, immediately after the battle, titled “A more full Relation of the great Victory Obtained by our Forces near Worcester“, contained an exact list of the Prisoners taken, and listed Colonel Benbow as one of the captured Colonels of Horse.

2. The Loyall Martyrology, by William Winstanley, published in 1665, just five years after the Restoration, shows a portrait wood cut of Col. Benbow, with the epitaph:

“Colonel Benbow, who for his Loyalty and superlative Valour, was by those blookthirsty Regicides, much about the same time shot to death at Shrewsbury.” (p.34)

3. The actual court martial record indicates that Captain Benbow was promoted to the rank of Colonel when he joined the Royalist forces in the summer of 1651. (The Stanley Papers, Cheltham Society, 1867)

Parliament decided to court martial him at his former rank in their army, rather than acknowledge his higher Royalist rank. This was a part of his punishment.

Clearly, Owen and Blakeway erred in their critique of Campbell and in the aspersions they cast on Paul Calton’s accuracy and honesty. Callender and Britton add that they even mistook the artist who painted the Admiral’s famous portrait which hung at the time in the Painted Hall of Greenwich; attributing the source of the engraving they commissioned by James Basire to Wageman rather than Godfrey Kneller.

However, Blakeway and Owen go on to claim that there were no estates held by the two Benbow brothers and that the name does not appear in lists of Nobleman and Gentlemen of the day. Furthermore, they initiate a search of the Herald’s College and conclude, as did the Naval Chronicle, that there is no evidence of an augmentation of arms. Unfortunately, they make another quantum assumption based on this, namely, that the Admiral did not use the Newport coat of Arms. They acknowledge that there was a Shropshire family who bore two bent bows and two sheaves of arrows but hold that the Admiral was not related to them. They conclude,

“This is another proof of the extreme incorrectness (to give the lightest term) of Mr. Calton’s communication.” (vol.ii, p.391)

Blakeway and Owen develop a family tree for the Admiral which starts with Lawrence Benbow of Prees, yeoman, whose son William they claim moved to Shrewsbury, married Eleanor and was admitted a burgher in 1628. They offer no substantiating evidence to support this link between the Cotton Hill Burgess and the Benbows of Prees. It is just as probable that the Cotton Hill Burgess who was a tanner was related to the Newport Benbows who also included tanners. Regardless, this couple have a son William Benbow at Cotton Hill who is baptised at St. Julian’s on October 15, 1615. This they maintain is the Admiral’s father. They list William’s brother John baptised at St. Julian’s on August 20, 1623 as the Captain John Benbow shot on October 16, 1651. This would make him a mere 28 years old when he attained Captain rank. It is remarkable that Archdeacon Owen who earlier described this Cavalier as a member of the Newport line should now place him in the Cotton Hill line, to fit Blakeway’s theory.

Sir John Laughton

Their point of view was accepted as fact by many subsequent authors. Sir John Laughton, in the prestigious Dictionary of National Biography, published in 1885 follows this view unquestioningly and joins the attack on Campbell and his source Paul Calton. As well he takes a most disparaging view of the Admiral himself. He describes Paul Calton’s information as “extraordinary misrepresentations” and “utterly untrustworthy” and describes him as

“foisting on Campbell’s credulity a romance, of which the greater part has not even a substratum of fact.” (DNB vol.ii, pp.210-211)

It is interesting that Sir Laughton, like Blakeway, places the Admiral in the Cotton Hill line and states he has no connection to the family who bore the Benbow coat of arms, yet still maintains he was nephew to that Captain John Benbow who was shot as a royalist in 1651.

Callendar and Britton, 1944

These two Benbow lines, the Newport and the Cotton Hill were somewhat disentangled in 1944 by Callender and Britton. They show by the Calendar of State Papers, Domestic, for 1651 that it was indeed Captain John Bendbow who was held a prisoner by Parliament and subsequently shot. They point out that though Campbell erred in naming him Colonel Thomas, there is evidence that he had a brother Thomas and both may have been Colonels in the Royalist Army.

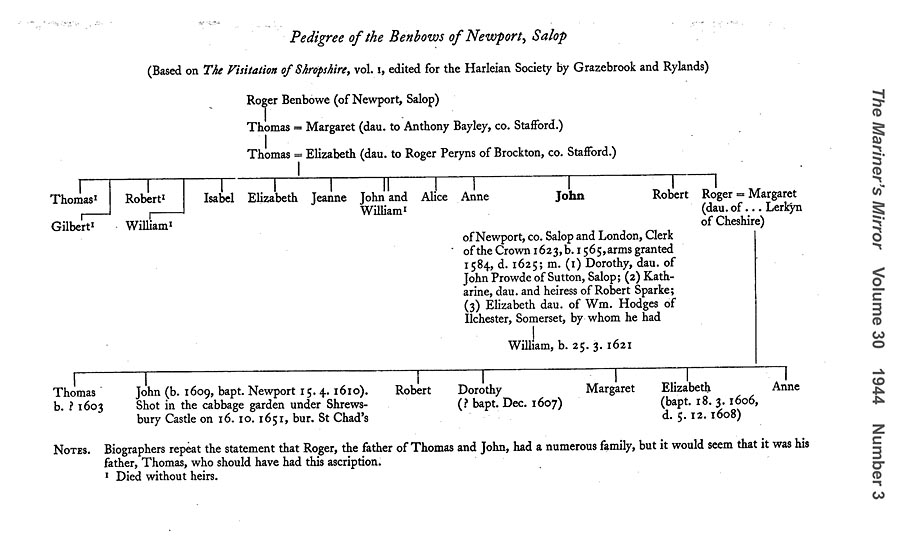

They further show that the 1623 Visitation of Shropshire (published 1889 by the Harleian Society) gives a Pedigree of the Benbows of Newport, Salop, which is remarkably like Campbell’s information which he received from Paul Calton.

“Here we find quite clearly set forth that John Benbow of Newport, Salop, and Deputy Clerk in Chancery, to whom armorial bearings were granted in 1584, was great-grandson of Roger Benbow of Newport and one of many children born to Thomas Benbow and Elizabeth Peryns of Brockton in the same county. One of John, the Deputy Clerk’s brothers was christened Roger after his great-grandfather, and married Margaret Lerkyn of Cheshire. This pair had seven children…the first born Thomas and his brother John, who was shot in the cabbage garden under Shrewsbury Castle and buried at St. Chad’s Church, 16 October 1651. (Callender and Britton, p.134)

They conclude that John Benbow the Cavalier was of the Newport line. However, they accept Blakeway and Owen’s theory that the Admiral was born to the Cotton Hill line. What then of the long tradition both local and written that he was nephew to the Cavalier. Callender and Britton try to solve this inconsistency by speculating that,

“there is the strongest probability that, when John Benbow the Admiral became world famous, he would in local estimation be indissolubly linked with John Benbow the romantic figure of the Great Civil War; the tragic circumstances of whose death seemed to foreshadow and anticipate his own.” (p.136)

My view

I am not persuaded.

I believe it is much more likely that Blakeway and Owen may have erred in assuming that they had discovered the Admiral’s sister Elenor’s baptismal record, and in so doing had irrefutably linked him to the Cotton Hill line. The tradition that he is of the Newport line has much more historical evidence both in the writings of his admirers and detractors. As mentioned earlier, in the earliest reference to his origins, the Dutch obituary of 1703 in the Historical and Political Mercury, it states that though his family were not of mean birth they were reduced because of their loyalty to the crown during the Civil War. And this information was clearly obtained from his widow Martha. Moreover the similarity of the 1623 pedigree and Paul Calton’s information is extremely persuasive. It is probable that the Admiral’s daughter Catherine told her husband of the family tradition concerning the brothers Thomas and John. The tale having passed from her grandfather to her father and then through her to her husband it is not surprising that precise relationships became blurred and names transposed. It is unlikely that Paul Calton could have fabricated information so close to the documented facts such as the names of John and Thomas. Such a background would help to explain how the Admiral managed to start his career in the Navy as a Master’s Mate and would also account in part for his rapid rise.

As well it is worth noting that there is substantial evidence he used a coat of arms. Callender and Britton are particularly helpful in describing this coat of Arms. They cite as the most important evidence an Alms Dish preserved in the Church of Milton near Abingdon. They describe it as follows:

“The silver alms-dish, which bears the London hall-mark of 1679-80, is engraved with the shield and crest of Benbow. It appears that Paul Calton, of the Manor House at Milton, who was baptised at Milton Church in 1664, married Catherine, a daughter of the famous Admiral John Benbow, and that she gave this dish to the church. She died in 1744. The dish has a deep depressed centre and a wide rim with a ribbed edge…The arms displayed on this silver dish may…be described as follows: Arms. Sable, two strung bows endorsed in pale Or, garnished Gules between two bundles of arrows, in fesse, three in each Or, barbed and tipped Argent, tied Gules. Crest. A harpy close Or, face proper, her breast pierced with an arrow Or. (p.137)

The dish remains still in the Milton Church, and the church wardens will upon request gladly display it. Callender and Britton point out that this coat of arms differs from that of the Naval Chronicle in that the latter has the bows front to front whereas the Alms Dish has them back to back, with the strings nearly touching. As well the Chronicle’s Crest has a wreath of red roses on the head of the harpy and lacks the golden arrow through her bosom. They point out that the Newport Benbow Arms as depicted in the 1623 Visitation have the bows back to back with the strings closest and the Harpy has a wreath of roses rather than an arrow through her breast. (They are unaware that the Benbow crest recorded in the College of Arms has an arrow in the Harpy’s bosom). They suggest that the Naval Chronicle erred in its rendition of the Arms due to a poor understanding of heraldry terminology. They also appear to be unaware that the Coat of Arms used on Benbow’s tomb in Kingston Parish Church is identical to the Naval Chronicle’s. Interestingly the tomb Arms differ from the Alms dish not only in having the bows reversed, but also in lacking the arrow through the Harpy’s breast. Examples of both versions of the Benbow crest must have been in contemporary use.

As the dish dates from 1680 and was donated to the Church by Catherine, the Admiral’s daughter, it is logical to assume it belonged to the Admiral and is an accurate representation of the Arms he used. Paul Calton’s statement that the Admiral was granted an augmentation of Arms consisting of an addition of arrows makes sense given the more recent responses from the College of Arms: namely that the officially recorded Newport Benbow arms consist only of two bows, and no arrows. Why then is there no record of this augmentation. Callender and Britton speculate that the Admiral may have applied to the College of Arms for such an addition to the Benbow Arms and have received a preliminary drawing but was possibly ordered to sea before completing the transaction. He may even have been encouraged by his King as Calton suggested. I would surmise, however, that it was offered not as a reward for his first West Indian expedition as Calton indicates, but rather as an unfulfilled promise for undertaking a second West Indian voyage.

Because Callender and Britton place the Admiral in the Cotton Hill line they assume he ‘borrowed’ Arms that were not his own, from the Newport line, and had them modified so as not to offend the rightful owners. This seems most unlikely given Paul Calton’s account as one is not likely to make a family tradition of such unethical ‘borrowing’. A more plausible explanation is that he was indeed entitled to use the Benbow Arms but either wished or was encouraged to make them more uniquely his own. I believe it is probable that King William led the Admiral to believe that he would be rewarded with a knighthood in return for his undertaking another hazardous voyage to the West Indies. This was a common reward granted to high naval officers following a successful campaign. In this particular case the King had some difficulty finding an Admiral willing to go to the West Indies. It would be natural for the Admiral to engage an artist to prepare an augmentation of arms. The death of King William and the Admiral’s own untimely end would terminate the project. However, his family and friends may well have seen to it that the proposed coat of arms was utilized in 1708 on his son’s stone in St. Nicholas Deptford, and on the silver plate donated to the Milton Church by his daughter.

The Admiral’s own use of a coat of arms is referred to by Nathan Dews in his History of Deptford where he describes the Admiral’s house with a coat of Arms over the door. (p.189) One further note about the coat of Arms. Callender and Britton mention that the Benbow Arms probably predate the confirmation to John Benbow, Chancery Clerk. In “A Display of Heraldrie” published in 1610,

“we find a medieval display of Arms, similar to those on the Milton Church alms dish with one exception; the bundles of arrows comprise eight weapons apiece. No family name is mentioned: but the author writes, ‘The field is Sable, two long bows bent in Pale, the strings counterpoised, Or, between as many sheaves of Arrows, banded, Argent. This coat standeth in Kirton (Crediton) Church in Devonshire. This sort of bearing may signifie a man resolved to abide the uttermost hazard of Battel, and to that end hath furnished himself to the full, as well with Instruments of Ejaculation, as also of Retention.'” (Callender and Britton, p.140)

William and Dorothy Berry, 2002

William and Dorothy Berry of Australia have done extensive research on the Newport Benbows, and published two essays: “The Two John Benbows“, and “The Benbow Family of Newport, 1500-1700″. They researched parish records, wills, pedigrees, land holdings etc. They acknowledge a serious gap in records due to the upheavals of the era. Consequently their conclusions are speculative. One, quite questionable belief is that the Colonel John Benbow shot as a Royalist is not of the Newport Benbow line.

They do uncover some interesting tidbits. For example, the Benbows of Newport were an important yeoman family who owned land, houses, and tenaments. There were several offshoots, one of which owned a tannery identified as Benbow’s yard on a 1680 map of Newport. This teases us with the possibility of a connection to the Shrewsbury Benbows who also owned a tannery. The last recorded Benbow appears to be Zachariah (Zachary) who died in Newport in 1698.

Other noted sons were two officials in Stuart administration. One of these was John Benbow, clerk of the Crown, whose coat of arms was recorded in 1622. John died in 1625 and left a will with 2000 pounds going to his son William (born 1621) on reaching the age twenty-one, together with a house and lands at High Offley and Aston, near Newport. The Berry’s were unable to confirm if William reached 21 and received his inheritance. They accept Callender and Britton’s comment on page 140 of their article that William died without children. However, no evidence is offered by any of these authors to substantiate this. The Berrys surmise that William’s inheritance passed to other members of the family.

The other public servant, John’s cousin Robert Benbow, was Clerke of the Petty Bag, or royal messenger. He was classed ‘delinquent’ by Parliament during the civil war as he accompanied the King when he fled London in 1642. He died at the King’s headquarters in Oxford in 1644. A portion of his estate was sequestered by the Parliamentarian authorities. His widow Joan was similarly ‘delinquent’ and hounded by creditors even after the Restoration. This certainly fits with Campbell’s information and that of the Political Mercury in terms of the Benbows suffering for their loyalty. The Calendar of State Papers in the 1660-1670’s refers to two messengers of the Great Seal and Exchequer named Robert and Thomas Benbow. These are probably sons of the Royalist Robert following in his footsteps, as was customary. They may have been granted their positions in recognition of their family’s loyalty and as partial restitution for their family’s loses.

The Berrys were unable to find ongoing records of the two sons of Roger Benbow, John and Thomas, who are traditonally held to be the Royalist Colonels referred to by Campbell. Consequently the Berrys erroneously conclude that the Colonel shot as a Royalist must not have been of the Newport line. The Berry’s accept Blakeway’s poorly supported conclusions that place Admiral Benbow in the Cotton Hill line. Strangely, like Blakeway, they do accept the part of Campbell’s account that has the Colonel as Admiral Benbow’s uncle, and therefore part of the Cotton Hill branch, and not part of the armourous Benbow’s of Newport. They appear to argue the Colonel’s lineage from their assumptions of the Admiral’s parentage. A strange circuitous logic. Their main support for placing the Colonel in the Cotton Hill line is his statement at his trial that he was from Shrewsbury. However, Newport is a but a few kilometres from the county seat of Shrewsbury, and it would not be surprising for Newport Benbows to migrate to Shrewsbury, particularly if they were militarily inclined. Being a resident of Shrewsbury does not negate being of the Newport Benbow heritage. And of course, the Cotton Hill line itself may be an offshoot of the Newport branch rather than the Prees line. It makes more sense to leave Colonel John Benbow in the Newport line where he has traditionally resided, as indicated in the footnote to the 1889 publication of the Visitation of Shropshire of 1623.

We do know definitively the pedigree of the Newport Benbow’s, and that John Benbow, Clerk of the Crown, was born in Newport in 1565, used a coat of arms that was officially recorded in 1622/3. He had three wives Dorothy, Katherine and Elizabeth. His duties brought him to London where the records of St.Martins in the Field suggest that he had five children, Ann in 1615, Robert in 1616, John in 1617, Margaret in 1618, (father listed only as Benbow) and William in 1621. Katherine told the Admiral’s first biographer, John Campbell, that her grandfather’s name was John Benbow. No doubt she became somewhat confused in recounting the family’s history when she came to the officer who was shot in Shrewsbury and who she had been told was the Admiral’s uncle. She naturally assumed her grandfather and her father’s uncle could not both be called John since they would be brothers. Her solution was to assume the captain who was shot was not named John but Thomas. The problem would not have existed if she had surmised that the captain was her grandfather’s cousin rather than brother. It would not be uncommon for the Admiral to think of his father’s cousin as a courtesy uncle. Katherine also told Campbell through her husband that her grandfather worked in the Tower of London at the time of his death.

Manning and Bray, 1804

An interesting statement is made in the HISTORY OF SURREY by Manning and Bray, in 1804.(vol.1. p.228) It states that Admiral Benbow was born not in Shrewsbury but in the London village of Rotherhithe, on Wintershull Street which was also known as Hanover Street, and is now Neston Street. This is located across the Thames and not far from the Tower, and thus supports Katherine’s account that her grandfather lived and worked in London following the Civil War. Parish records of the area show several Benbows at that time, but are incomplete, as are many church records of that period. It is probable that the Admiral was born in Shrewsbury, but raised in London following the Restoration when his father obtained employment in the Tower. He may have been sent home to Shrewsbury following his father’s death, to be raised by relatives and attend the free school.

Conclusion

There are thus two theories of the Admiral’s ancestry. The first hypothesis links him to the ancient armorial Benbows of Newport and was first raised in the 1703 account in the Political Mercury. In the 1740’s his daughter Katherine and her husband Paul Calton, relate details of this lineage to Benbow’s first biographer Dr. John Campbell. The Newport Benbows were at one time landed Shropshire yeomen or lesser gentry. A leading member of this family, John Benbow Deputy Clerk of the Crown in Chancery, used a coat of arms that was officially recorded in 1622/3. He is buried in the parish of St. Martins in the Field, London. It is highly likely that Admiral Benbow used a coat of arms very similar to that used by the Newport Benbows. No record of the Admiral’s birth has been found so we do not know the precise details of his parentage. The Civil War obliterated many parish records and indeed made it difficult to register baptisms. The Admiral’s other link to this family is the widely held belief that he was related to the Cavalier John Benbow who was shot as a Royalist in 1651 very close to the time of the Admiral’s birth. A connection to London has been suggested by both his daughter and subsequent lore.

The other theory suggests that he is of the Cotton Hill line and was first referred to by T. Phillips in 1779 and later supported by Hugh Owen in 1808 and in 1825 by Blakeway and Owen. They based their assertions on the 1724 gravestone inscription of the Admiral’s sister Elinor and a baptismal record of a similarly named person dated 1646 which gives her father as William Benbo. There is ample evidence that William Benbow, the tanner of Cotton Hill did indeed have a daughter Elianor born about that year. Whether this is the same Elinor as that buried in 1724 is not established. Blakeway and Owen make the assumption based on the similarity of age and name. The Cotton Hill line does not likely include the Cavalier shot in 1651. Although Blakeway derives the Cotton Hill Benbow’s from Prees, it is just as possible that they are connected to the Newport Benbows, through their tannery businesses. There is a local Shrewsbury tradition that Admiral Benbow was the son of a tanner and ran away to sea leaving his house key on the tree in front of the tannery house on Cotton Hill.

I believe the weight of evidence still leans towards the Newport line and that this account is more consistent with both oral and written traditions. Campbell’s account holds up well to recent historical analysis and research. The mystery, however, remains.