CAPTAIN BENBOW’S FIRST ADVENTURE: SCRIMSHAW by K.D. (DENNIS) HOLLAND

Benbow’s first biographer, John Campbell, tells the tale of Captain Benbow’s first Adventure. The British had pulled out of Tangier in 1684, leaving it to the Moroccans. The Mediterranean was again overrun with North African pirates. In 1686 Captain Benbow, in his own vessel, the Benbow frigate, was attacked on the way to Cadiz by a Sallee rover. The Benbow, though unequal in the number of men, fought bravely, but could not hold off the enemy. The Moors grappled and boarded the Benbow but soon realized their error as Benbow rallied his crew and fought so fiercely that the pirates fled, leaving behind thirteen of their mates. Captain Benbow ordered their heads cut off and pickled so that he could collect the bounty on pirates and also play a rather ghoulish practical joke on the Spanish Revenue officials at Cadiz with which he had numerous altercations on the subject of duties. His behaviour is reminiscent of West Indian pirates who used similar tactics to develop a reputation which would strike terror in the hearts of their enemies.

He landed at Cadiz and had his African servant, Caesar, carry the sackful of heads. He pretended to take it ill that the customs men wanted to view the contents and would not accept his word. He claimed they were ‘salt provisions for my own use’. The customs agents insisted on seeing the contents and indicated that only the magistrates could grant any dispensation. So they went off to the custom-house, Benbow in the front, his man in the centre, and the officers in the rear. The magistrates treated Captain Benbow very civilly, and said they were sorry to make a point of such a trifle. However, they were obliged to demand a sight of the contents, and as they doubted not that they were indeed salt provi-sions, the showing them could be of no great consequence one way or other. “I told you,” retorted Benbow, “they were salt provisions for my own use. Caesar, throw them down upon the table; and, gentlemen, if you like them, they are at your service.” The Spaniards were suitably impressed at the sight of the Moors heads, and that Benbow had been able to defeat such a number of barbarians with so small a force. They sent an account of the matter to the Spanish King, Charles 11, at Madrid, and he sent for Benbow. He was so taken with the Englishman that he not only gave him a handsome present but wrote on his behalf to the English King James. According to Campbell, it was due to this adventure that Benbow was again offered a commission in the royal navy. Even Blakeway and Owen accept this Calton tale as probable on the basis of a Moorish skull cap which was in the possession of descendants of Richard Ridley, husband of the Admiral’s sister Elizabeth . The cap is inscribed:

“The first Adventure of Capt. John Benbo and gift to Richard Ridley, 1687.” (Blakeway and Owen, vol.ii, p.392)

BATTLE OF BARFLEUR, 1692 – SCRIMSHAW by CHRIS LEEWALDER

A depiction of an action that took place in 1692 during the War of the English Succession, between the French and Anglo-Dutch fleets. The latter was at sea in the Channel in May 1692. Some historians, particularly, John Laughton in the Dictionary of National Biography, claim that Captain John Benbow served as Master of the Fleet during this campaign. The French Comte de Tourville was in Bertheaume Bay awaiting a large reinforcement from Toulon. His force was intended to convoy the French invasion fleet which was to put James II back on the English throne. On 17 May he left his anchorage and with 44 ships of the line went in search of Edward Russell, the British commander-in-chief. However, he was inferior to the Anglo-Dutch fleet with a force of less than half their strength, which included 99 ships of the line. He acted rashly by attacking the allied centre and rear. The Dutch were in the van and so were not engaged, and Russell ordered them to double-back. Although the French fleet fought hard they were only saved from destruction by the poor visibility, which became too thick for general fighting in the early afternoon.

The Battle of Barfleur was the prelude to a French disaster. This partly stemmed from Tourville’s impatience in not awaiting the arrival of d’Estrées, with his squadron from Toulon. During the evening of 19 May, the wind freshened and the pursuing allies came into partial action again. It was at this point in the battle that Richard Carter, Rear-Admiral of the Blue Squadron, was killed. Throughout 20 May, the chase to the west continued and on the following morning at 11.00 the French ‘Soleil Royal’, 106 guns, went aground near Cherbourg, Tourville having already disembarked. Together with the majority of his fleet, Tourville took refuge in the Bay of La Hogue. Sir Ralph Delavall’s initial attempt to destroy the ‘Soleil Royal’ and the two large ships with her, the ‘Admirable’, 90 guns, and the ‘Triomphant’, 74 guns, was repulsed. However on 22 May, he renewed his attack with his boats and destroyed all three. The same day the rest of the fleet worked its way into the Bay of La Hogue to get within striking distance of the rest of the French fleet. The next day, Monday 23rd, the boats of the fleet were ordered in under Vice-Admiral George Rooke in the ‘Neptune’, 96 guns. The French ships were so close to the shore that the French cavalry rode into the water to protect them. Altogether, 12 French men-of-war were destroyed, together with several transports. With the destruction of so much of Tourville’s fleet, the threat of invasion disappeared.

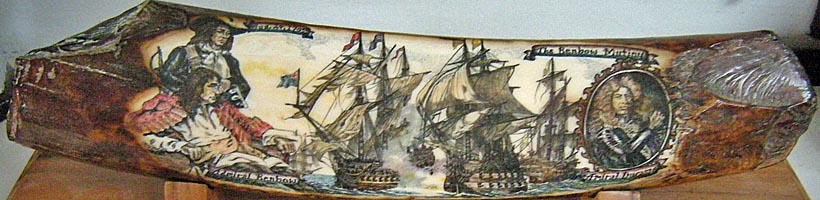

BENBOW’S LAST FIGHT, 1702 – SCRIMSHAW by PAUL SHELDON

Hawaiian scrimhandler Paul Sheldon has captured a wounded Admiral Benbow in his cradle on the quarter deck, continuing to conduct his last battle against French Admiral Du Casse depicted in the right cameo.

BATTLE OF FLAMBOROUGH HEAD, SEPTEMBER 23, 1779 – SCRIMSHAW by JIM DUCOTE

On the evening of 23rd September 1779 crowds of people on the Yorkshire Cliffs watched one of the most stubborn naval battles in British history. The battle was between the American squadron of John Paul Jones and two British ships of war.

Jones was supplied with a small squadron of ships comprised of Bonhomme Richard with 40 guns, Alliance a frigate with 36 guns, the Pallas a French ship of 32 guns, the Cerf with 18 guns and the Vengeance with 12 guns.He spotted a fleet of forty-one merchantmen from the Baltic escorted by two British warships, the Serapis and the Countess of Scarborough, bearing NNE.

When the British fleet saw the squadron bearing down on them, they set sail for the refuge of the shore. The two British warships steered to intercept the American squadron and prepared for battle. All afternoon the American ships manoeuvred to get between the convoy and the land. At seven o`clock, with a full moon, the Bonhomme Richard found herself facing the Serapis. The English ships had succeed in their aim of getting between the Americans and the convoy.

The battle was intense and Jones, recognising his ships’ inferior strength, sought to keep the battle at close quarters. In the close battle the Serapis struck into the Bonhomme Richard and Jones took the opportunity of making both ships fast. The battle continued fiercely with the ships locked together. A bloody close battle developed with both ships being badly damaged and many of the crew of both ships being killed or wounded. By 8 o’clock the Bonhomme Richard was leaking badly.

During the later stages of the battle the Alliance came up to join in but incredibly fired first at the Bonhomme Richard, instead of at the Serapis and did considerable damage, before firing at the Serapis. The Bonhomme Richard was an almost shattered wreck but the Serapis was in a worst state as the Alliance gave her the same attention that it had given the Bonhomme Richard.

Captain Pearson of Serapis gave up his gallant defence as he believed that no further good could result from continuing the combat now that the Alliance had joined in. He surrendered his sword to John Paul Jones on the deck of the Bonhomme Richard and the battle was over.

THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR, 1805 – SCRIMSHAW ENGLISH

The Battle of Trafalgar was considered to be the greatest sea battle with sailing ships. It was also the last. It took place just off the coast of Cape Trafalgar between Caños de Meca and Conil on the Costa de la Luz.

At this time, Napoleon was allied with Spain and reigned supreme in Europe. He was planning an invasion of Britain, but to do this, he needed to be sure of his supremacy on the seas.

The British fleet was commanded by Admiral Horacio Nelson and the combined Franco/Spanish fleet by General Villeneuve.

For two years, the two fleets chased each other around the Atlantic, the West Indies and the Mediterranean, before finally coming together for the Battle of Trafalgar. Communication and intelligence information at the time was slow and difficult. It could be weeks before a vital piece of information reached its destination, with the result that by the time it arrived, it was often hopelessly out of date.

On the 14th August, Villeneuve left northern Spain for Brest but later changed course southwards. On 20th August, he led thirty-nine Franco/Spanish Man o’ War ships past four British ships and into the Bay of Cadiz.

Napoleon directed Villeneuve to leave Cadiz for Toulon at the first favourable opportunity. Whilst Villeneuve waited, Nelson arrived onboard the Victory, providing valuable reinforcement for the British.

Napoleon sent Admiral Rosily to relieve Villeneuve of his command. It took him ten days to travel by road from Madrid to Cadiz. Villeneuve knew it was time to leave the Bay.

Villeneuve formed a battle line three miles long with his forty ships. The fleet sailed ahead very slowly and Nelson hoisted a flag signal “England expects every man to do his duty”.

Nelson’s thirty-three ships split into two columns rather than forming the customary parallel battle line, so avoiding the typical long strung-out battle which had been practiced for centuries. This bold strategy caused confusion and resulted in a series of smaller, single combats of bloody ferocity.

Nelson paced the quarterdeck, the ribbons of his jacket ablaze with colour, urging his men on. It was during this battle that a French sniper fatally wounded him. Nelson was immediately taken below decks and the great man uttered his famous dying words “Thank God I have done my duty”.

Of the thirty-three allied ships engaged, seventeen had surrendered during the Battle and many others were damaged and sunk soon afterwards.

Of the forty ships to leave Cadiz, only ten returned. More than 4500 allied lives were lost.

The English had far fewer casualties, but had lost their best and beloved admiral, Admiral Nelson.

The British ships limped back to the safety of Gibraltar. The Gibraltar Chronicle carried its greatest world exclusive the next day. Nelson’s body was brought ashore at Rosia bay and placed in a brandy vat in preparation for the long journey back to England. The sailors who lost their lives were buried at sea. Those who survived the battle but who later died of their wounds, were buried in the Trafalgar Cemetery in Gibraltar.

Without a navy, the allied forces were no longer in a position to attack the British Isles.

Despite the magnitude of this battle, many historians argue that the fate of the Napoleonic wars were sealed at Cape Trafalgar, and not at Waterloo, ten years later.

USS ENTERPRISE vs HMS BOXER, 1813 – SCRIMSHAW NEW ENGLAND

DATE: September 5, 1813

VICTORY: American

COMMANDERS: Lt. William Burrows (American)/ Capt. Samuel Blyth (British)

CASUALTIES:

AMERICAN……………. (102 men) 2 -KILLED/ 10 -WOUNDED

BRITISH/INDIANS…… ( 66 men) 3 -KILLED/ 17 -WOUNDED

BATTLE DESCRIPTION:

The American ship, USS Enterprise, was under the command of Lt. William Burrows. In the way of weapons, it carried 16 carronades, and she had a crew of 102 men.

On September 5, the Americans spotted a ship which proved to be the H.M.S. Boxer. The British ship was under the command of Capt. Samuel Blyth. The Boxer had 14 carronades and a crew of 66 men.

When the Boxer first spotted the Enterprise, the crew hoisted 3 British flags and headed for the Enterprise. When the 2 ships were still some 4 miles away from each other the wind died down. The wind picked up again around noon, and the 2 ships manuvered for position. The Americans hoisted their flags at about 3:00 P.M. and moved slowly toward the British ship. Blyth had ordered the British flags nailed to the mast, and told his crew that they should not be lowered while he was still alive.

At 3:15 P.M., both ships opened fire, as both crews cheered wildly. The battle was intense, with both commanders falling early. Blythe was struck by an 18-pound shot and killed instantly. Lt. David McCreery was now in command of the Boxer. Burrows was wounded severely. In spite of great pain, he refused to leave the deck, instead he cryed out that the flags must never be lowered.

At 3:30 P.M., the Enterprise came around and raked the Boxer. About 5 minutes later, the Boxer lost her main-top mast and top-sail yard. The Enterprise moved into position and began to deliver broadside after broadside that raked the Boxer’s deck. Boxer’s crew fought bravely on, except for 4 men who were later court martialed for cowardice. At 3:45 P.M., unable to manuver the defenseless ship, the Boxer surrendered.

Both ships had been damaged severely, but the British ship had suffered more. Burrows, after he receieved the sword of the British commander said: “I am satisfied, I die contented.”

USS Constitution vs HMS Guerrier 1812 – SCRIMSHAW by YOKO GAYDOS AND PAUL SHELDON

On August 2nd 1812 the “Constitution” set sail departing from Boston and sailed east in hopes of finding some British ships. After meeting no British ships, the “Constitution” sailed along the coast of Nova Scotia, and then Newfoundland, finally stationing off Cape Race in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. It was here that the Americans captured and burned two brigs of little value. On August 15th the “Constitution” recaptured an American brig from the British ship-sloop “Avenger”, however the British ship managed to escape. Captain Isaac Hull put a crew on the brig and they sailed it back to an American port.

At 2:00 p.m. on August 19th the crew of the “Constitution” made out a large sail which proved to be the British frigate “Guerriere” captained by James Dacres. At 4:30 p.m. the two ships began to position themselves and hoisted their flags (colours). At 5:00 p.m. the “Guerriere” opened fire with her weather guns, the shots splashed in the water short of the American ship. The British then fired her port broadsides, two of these shots hit the American ship, the rest went over and through her rigging. As the British prepared to fire again the “Constitution” fired her port guns. The two ships were a fair distance apart, and for the next 60 minutes or so they continued like this with very little damage being done to either party.

At 6:00 p.m. they moved closer, at 6:05 p.m. the two ships were within pistol-shot of each other. A furious cannonade began, at 6:20 p.m. the “Constitution” shot away the “Guerriere’s” mizzen-mast, the British ship was damaged. The “Constitution” came around the “Guerriere’s” bow and delivered a heavy raking fire which shot away the British frigate’s main yard. The Americans came around yet again and raked the “Guerriere”. The mizzen-mast of the British ship was now dragging in the water and the two ships came in close to each other. The British bow guns did some damage to the captain’s cabin of the “Constitution”, a fire even started there. An American officer by the name of Lieutenant Hoffmann put the fire out.

It was about here that both crews tried to board the others ship, or at least thought about it. And it was also here where most of the “Constitution’s” casualties were taken. In fact both sides suffered greatly from musketry at this point. On the “Guerriere” the loss was much greater. Captain James Dacres was shot in the back while cheering on his crew to fight. The ships finally worked themselves free of each other, and then the “Guerriere’s” foremast and main-mast came crashing down leaving the British ship defenceless.

At 6:30 p.m. the “Constitution” ran off a little and made repairs which only took minutes to complete. Captain Isaac Hull stood and watched at 7:00 p.m. as the battered British ship surrendered, unable to continue the fight.

The “Constitution” had a crew of 456 and carried 44 guns. The Guerriere had a crew of 272 men and carried 38 guns. The American casualties were 14, which included Lieutenant William S. Bush, of the marines, and six seamen killed. And her first lieutenant, Charles Morris, Master, John C. Alwyn, four seamen, and one marine wounded. Total seven killed and seven wounded. Almost all the American casualties came from the enemy musketry when the two ships came together. The British lost 23 killed and mortally wounded, including her second lieutenant, Henry Ready, and 56 wounded severely and slightly, including Captain Dacres for a total of 79. The rest of the British crew became prisoners.

ACTION OF AUGUST 1702 – SANTA MARTA – THE BENBOW MUTINY – SCRIMSHAW NEW BEDFORD, NEW ENGLAND, Scrimshaw by Susan Lajoie

RUSSIAN ACTION – SCRIMSHAW RUSSIAN

PIRATE CAPTAIN – SCRIMSHAW by TINA WHITE

Kirkby Courtmartial 1702 by Yoko Gaydos on Mammoth Ivory

Return to Top