Captain Benbow was Master of the Fleet in one and possibly two of the most significant naval actions of King William’s War (War of the English Succession) between England and France 1689 to 1697. In May of 1690 he was Master of Admiral Herbert’s flagship, the Royal Sovereign.

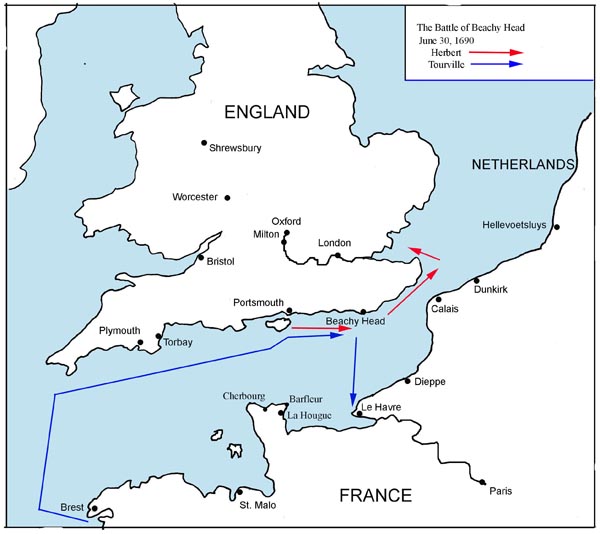

BEACHY HEAD

In this capacity Benbow was responsible for navigating the fleet, seeing that it got into position for battle and managed to keep its line in response to the wind, current and tide. He would be one of the main staff officers advising Herbert as the battle unfolded.

The French under Admiral Comte de Tourville left Brest on June 13 with a fleet of 76 warships in three squadrons, plus frigates, store ships and 18 fire ships. Fire ships were smaller ships designed to be set ablaze and crash into the enemy. The French fleet cruised up Channel, and on June 23 were off the Isle of Wight when they sighted allied ships.

Herbert’s fleet numbered only 34 English and 21 Dutch ships. Seeing himself so outnumbered, he let his fleet drift Eastward up the Channel on the flood, hoping for reinforcements. His fleet was divided into three squadrons: the Dutch or White squadron in the Van or front of the battle line, the rear or Blue squadron under Sir Ralph Delavalle, and the Red or centre commanded by himself.

The two fleets moved slowly up Channel. Herbert had wanted to avoid a battle which he could easily lose for fear that James II, with his army gathering at Brest for an invasion of England, would be able to cross the channel without opposition were the fleet to be lost. He argued strongly to ensure the maintenance of the “fleet in being” .

Unfortunately Herbert’s rival, Russell, back in London, was able to persuade the Queen to order Herbert to attack. So at dawn on June 30, on the ebb tide, and with the wind from north-north-east, Herbert reluctantly bore down towards the French. The Dutch van, under Evertsen pressed home the attack with their 21 ships against the French van of 26. There were great gaps between the allied squadrons, with their line attenuated in order to cover the French line and prevent a doubling up by the French on allied ships at either end.

The French van or leading ships managed to double on the Dutch and place them between two fires. Delevalle in the rear took his greatly outnumbered blue squadron to within musket shot (300 yards) of the French rear. But Herbert’s Red squadron was for the most part ineffectual and out of range in the centre.

At five in the afternoon, after an engagement of eight hours, the English anchored with all sails set as the ebb tide began to make. The French were caught unaware and drifted out of range with the tide. Later in the evening, when the flood of the tide set in, Herbert resumed his retreat towards the Thames estuary. The Dutch had been badly mauled. The allies lost up to 14 ships, mostly Dutch, Tourville lost no ships at all. Benbow, as Master of the Fleet, is credited with saving the fleet with his brilliant seamanship. There was almost no wind, and the fleet slowly retreated up channel by skilfully ‘working the tides’.

This engraving of a Gudin painting is another French illustration of the battle: the English did not memorialize it. The King and Queen blamed Herbert for the losses, and sent him to the Tower. At his court martial in December he argued that the Dutch had gone into action too soon. And that by retreating he had maintained the ‘fleet in being’, thus preserving the realm by preventing a subsequent French landing. A telling witness was Captain John Benbow, who hotly defended his mentor’s courage and integrity. In his preliminary deposition in July, he testified as master of the fleet at Beachy Head: he argued that Herbert had brought the Sovereign to within one half gun shot of the enemy for over an hour. Like Benbow, 20 of the 27 officers on the court martial had been mentored by Herbert. Not surprisingly, Herbert was acquitted. But he was still dismissed from all his offices and never employed at sea again.

EDWARD RUSSELL TAKES COMMAND

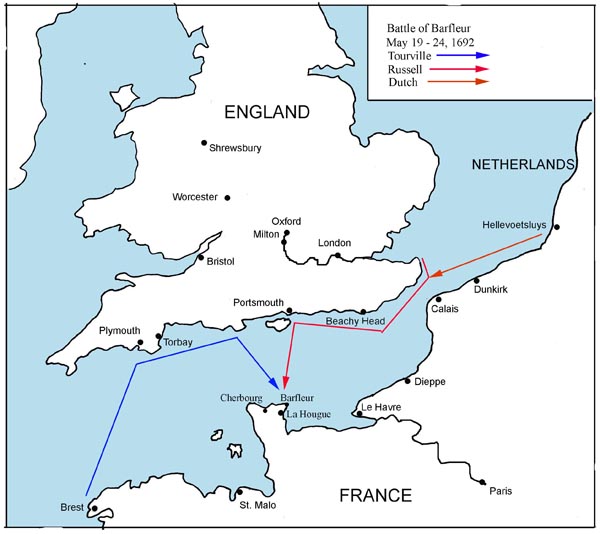

BARFLEUR

The English realised victory at sea was a matter of numbers, and in October 1690 the English Parliament voted over half a million pounds for building 27 new warships. Edward Russell, later Earl of Orford, was appointed sole commander of the fleet. Benbow returned to the Deptford dockyard and his task of outfitting the growing fleet. His position as one of the Navy’s senior professional seamen remained secure.

John Laughton, in the Dictionary of National Biography, states that in the Spring of 1692 Benbow, on board Russell’s flagship the Britannia, was again Master of the combined Anglo Dutch Fleet comprised of 82 ships of the line. On May 19 the French under the Comte de Tourville approached Russell’s fleet with only forty-five ships of the line near Cape Barfleur on the Normandy coast. In the hazy weather he did not realize the size of the allied fleet and so rushed to engage hoping for another Beachy Head.

The van of the French hotly engaged the Dutch and their centre and rear furiously assaulted the red squadron led by Russell himself. For the moment the French actually outnumbered the English ships they were attacking as the blue squadron under Rooke was a good deal astern or behind and three miles to leeward or down wind. It would take some time for them to join the battle by sailing as best they could against the wind. In the Britannia Benbow would be in the thick of things, closely engaged by Tourville in the Soleil Royal. Finally a wind change permitted the rear of the red or centre squadron under Shovell to break through the French line. The Dutch at the head of the line doubled the French van, trapping it with fire on both sides. Shortly after, the whole of the blue squadron under Rooke broke the French rear. In late afternoon, fog stalled the battle and the French fled in disorder.

This unusual illustration of the Battle of Barfleur is Scrimshaw on Mammoth Ivory, by Chris Lehwalder, after a painting by Backhuysen. It shows the Soleil Royal surrounded by Dutch and English including the Britannia on its right. Three French ships, including the Soleil Royal, were burnt at Cherbourg by Delaval. Several French ships escaped further westward past Cap de la Hague and through the treacherous waters of the Alderney Race. The English feared to follow without a competent pilot. The Britannia had followed the enemy ships fleeing to the East. These took refuge in the bay of La Hougue where James’ invasion army was awaiting transport. James’ flag flew over the fort of St. Vaast signalling his presence.

Russell blockaded the bay and on May 23 and 24 sent in two hundred boats and fire ships under the command of Rooke . It is quite likely that Captain Benbow accompanied Rooke, since he was quickly acquiring a reputation for piloting in Channel waters. The English had to brave the cannonade from the forts, musket fire from the beach and ships boats and even some French cavalry who waded into the surf. Nevertheless they succeeded in burning twelve ships of the line and eight or ten transports. On the cliffs above, James watched the destruction of his hopes for an invasion. The Battle of Barfleur was not considered a complete success. Russell was thought to have engaged the enemy in a half-hearted manner; thus allowing too many of the French to escape. He was removed from the command and replaced by a triumvirate of Admirals: Delavalle, Killigrew, and Shovell. Benbow was rewarded for his part by a special Admiralty order which directed he be paid both as Master of Deptford Dockyard and as Master of the Fleet.

The Channel War

Machine Vessel or ‘Infernal’ Vesuvius From Marine, Diderot/D’Alembert The French response to the major loss of Barfleur and La Hougue was to develop a new and highly successful naval strategy of waging war against English and Dutch merchant shipping. The Channel ports along the French coast spawned hosts of wolf packs of privateers or as the French called them: corsairs.

The English answer was to attack the corsair bases. Benbow’s dash and enterprise in these operations made him into a national hero, especially with the mercantile community Because of the difficulty of causing any real damage to these fortified ports, from the sea, the English developed a new weapon: a ship full of explosives, called an ‘Infernal’. This was a converted fireship, loaded with several tons of powder in casks, over which was placed a load of bombs, old cannon and scrap-iron.

One of Benbow’s earliest expeditions utilizing these new ‘machines’ occurred in the fall of 1693. He was ordered to accompany the fleet’s chief military engineer,Captain Thomas Phillips, in an attack on St. Malo This triple portrait shows Engineer Phillips holding a plan of fortifications, Benbow in the centre with a quadrant, and their admiral, Sir Ralph Delavalle, Admiral of the Blue. The placing of Benbow in the centre suggests that he had probably commissioned the work. The painting thus shows how he wished to be portrayed: as the essential element between the technical armourer and the naval hierarchy; and as the one who could deliver the goods. He also could be reaching out to Delavalle as a patron, now that he has lost Herbert and Russell was out of favour. Interestingly, after the death of Phillips, the painting was copied, and a reinstated Admiral Russell took Phillips place on the left.

ST. MALO 1693

This 1693 French chart of St. Malo harbour shows the positions of the attacking ships including the Admiral, the ships of the line, the frigates, the bombs, and the machine. The chart illustrates quite well the difficulty of navigating through the sand banks and rocks. Commodore Benbow led a squadron of 12 warships, four bomb vessels, and ten brigantines. The attack began on the 16th. The bomb vessels threw about seventy bombs a day into the town. On the 19th Captain Phillips took in the Vesuvius, an extraordinary fire ship of 300 tons full of explosives, which was intended to have reduced the town to ashes. Unfortunately it grounded on a rock within pistol shot of its destination (forty metres) and was exploded there. This shook the town like an earthquake, breaking all the glass within three leagues and blew off the roofs of three hundred houses. As well the greatest part of the sea wall was destroyed. A French account describes the explosion as terrible beyond description. Benbow captured an out-lying fort taking 80 prisoners and 60 cannon, burnt 30 privateers, many merchant ships and transport vessels and set the town on fire in many places. It was reported that the great cathedral at St. Malo was laid in ashes. Unfortunately, Captain Phillips was mortally wounded.

DIEPPE 1694

Over the next couple of years while serving under Admiral Berkeley, Benbow led the attacks on most of the Channel ports.

In July 1694 they successfully bombarded Dieppe . About eleven hundred bombs and incendiary carcasses were fired on the town which was set on fire in several spots. The Nicholas machine vessel was exploded against the town pier. When the squadron departed most of the town was in flames and was largely destroyed. This antique engraving is taken from a 1701 German book and shows the explosion of the Nicholas against the town wall.

Another view of the mortar bombardment of Dieppe is shown in this 1735 engraving.

Colonel Richards succeeded Phillips as the fleet advisor on mortars and bombs. This vivid night scene credits Colonel Richards, with the development of these bomb vessels. A Dutch engineer and inventor, Willem Meester, was also instrumental in promoting the ‘Machine’ vessels like the Nicholas. Throughout 1694 Captain Benbow commanded the in-shore squadron of bomb vessels and machines against the French channel ports including Le Havre, La Hogue, Cherbourg, Dunkirk and Calais. Return to Top